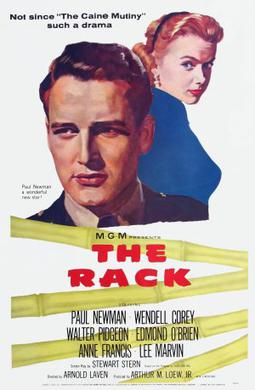

“The

Rack” is a Korean War courtroom drama that deals with the collaboration of

American prisoners of war. It was

directed by Arnold Laven who was noted more for directing TV programs. In fact, the movie was based on a teleplay by

Rod Serling. The teleplay appeared on a

show called “The U.S. Steel Hour”. Oh,

the Fifties. Knowing it came from

Serling tells you it is not going to be predictable. The movie was meant to be MGM’s answer to

“The Caine Mutiny”. Glenn Ford was

offered the lead, but turned it down because he thought the main character

chewed the scenery too much. Instead it

went to a potential star – Paul Newman.

Good prediction as the movie’s release was delayed until after “Somebody

Likes Me” came out and his career took off.

The

movie opens at the close of the Korean War.

Capt. Edward Hall (Newman) is greeted at the air field by his father

(Walter Pidgeon) and his sister-in-law Aggie (Anne Francis). His father is a retired colonel who has

already lost a son, Aggie’s husband, in the war. The reunion is awkward. Edward, Jr. is reluctant to go home from the

hospital and is obviously holding something back. A clue is when a fellow POW slips a noose

labeled “traitor” around his neck. It

turns out that Edward is one of forty POWs that are up on charges for

misconduct. What follows is a standard

court-martial, but with Rod Serling twists.

The trial is intercut with Edward’s uncomfortable relationship with his

father, who at one point wishes that his son had died.

“The

Rack” is interesting. The set-up is

similar to “Time Limit”, but the trial does a better job outlining the case for

and against leniency for collaboration.

There are three fellow prisoners who offer evidence that Hall gave

propaganda lectures, wrote leaflets encouraging soldiers to surrender, and ratted

out an escape attempt. One of them is a

Capt. Miller (Lee Marvin, perfectly cast) who describes himself as a

“reactionary” and Hall as a “progressive”.

In other words, real American versus communist sympathizer. The rest of the cast is equally effective in

the main roles. Anne Francis is realistically

torn as the sister-in-law who has to act happy that Edward is back when she

wonders why he survived when her hero husband died. The prosecuting Maj. Moulton (Wendell Corey)

and defending Lt. Col. Wasnick (Edmund O’Brien) are well-played. Moulton is not dastardly. He is not Saint-Auban from “Paths of Glory”. Walter Pidgeon is the weak link, but it is due

to his character being weak. Col. Hall

is surprisingly clueless about his son’s situation and then goes through a

typical cinematic reconciliation. Newman

has a star turn and although his Rocky Graziano biopic launched his stardom,

this movie was the first evidence that he was special.

The

movie is essentially a play, but the cinematography does have some nice deep

focus. The real strength is the

dialogue. Edward counters his father’s

disappointment with “my mother wasn’t in the Army, so I’m a half-breed”. He explains his collaboration by saying that

he “sold [his] soul for a blanket that smelled like urine and three hours of

sleep.” The script is

thought-provoking. You wonder what you

would have done under the circumstances.

You will also wonder if he is guilty and whether he will be found

guilty. The movie is not predictable.

If

you know little about the Korean War prisoner experience, “The Rack” is a good

primer. The movie takes its instructive

potential seriously. It covers communist

tactics used to turn prisoners and some of the things the collaborators

did. Hall is a poster boy for them. It also covers why some soldiers collaborated

and whether some actions were excusable. If you didn’t already know it, the

Korean War was one fucked up war.

GRADE

= B

HISTORICAL ACCURACY: “The

Rack” does not claim to be based on a true story. The scenario is realistic, however. There were about 7,500 Americans captured in

the war. 2,500 did not survive captivity

due to lack of food, lack of medical care, freezing conditions, and mistreatment.

Shockingly, 21 Americans refused to be repatriated. The American public learned a new term –

brainwashing. This political

indoctrination has been exaggerated by movies like “The Manchurian Candidate”,

but collaboration was a problem. Hall

did not collaborate because of brain-washing.

He gave propaganda lectures, wrote leaflets, and ratted out comrades

because of tactics like sleep deprivation and solitary confinement. These types of tactics, along with physical

brutality, were effective because some of the Americans were susceptible to

them. The movie has the defense

summarize a communist communique:

1. many POWs reveal weak

loyalties to families, communities, and the Army 2.

when left alone they tend to feel deserted and underestimate their ability

to survive because they underestimate themselves 3.

even college graduates know little about American History, democracy,

and communism. Hall was part of an

“uninspired, uninformed, unprepared” generation. But did that excuse collaboration? The Pentagon unofficially acknowledged the

problem by establishing a committee to come up with a set of rules for conduct

as a prisoner. Pres. Eisenhower issued

Executive Order 10631 creating the “Code of U.S. Fighting Force” in 1955. It responded to situations like what the

fictional Hal went through by proclaiming that you must avoid collaborating

until “all reasonable means of resistance are exhausted and … certain death is

the only alternative.” You must “resist

by all means available.” As the prosecution

asks of Hall: “did you ever reach your

horizon of unendurable anguish?” Because

of the code and better training, collaboration was less of a problem in

Vietnam. And because of the fictional

Hall and the large number of real prisoners who faced trials when they

returned, the military and the public became more understanding. John McCain would have been in Hall’s shoes

if he had been a captive in the Korean War.

Watch “Faith of My Fathers.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please fell free to comment. I would love to hear what you think and will respond.