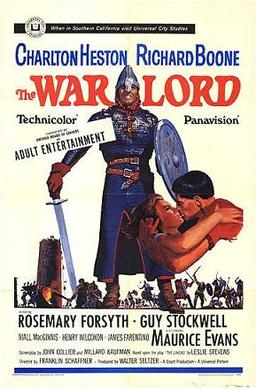

“The War Lord” is a different type of medieval

movie. It was a personal project for

Charleston Heston who optioned the play “The Lovers” by Leslie Stevens. He got Franklin Shaffner to direct it. This was three years before he teamed up

again with Heston for “Planet of the Apes” and five years before “Patton”. The film was an attempt to bring a more

authentically gritty view of the Middle Ages.

It is one of the rare medieval movies that are not epic in scope. This might partly explain why it did not do well

at the box office.

Orson Welles narrates that in 11th Century

Normandy powerful dukes ruled their lands and provided protection from

Viking-like raiders called Frisians. A

knight named Chrysagon (Heston), fresh from a Crusade, has been given charge of

a Druid village. He and his band of

knights-errant arrive just in time to kick some Frisian ass. Chrysagon duels with the Frisian leader, but

he gets away. Chrysagon is less than

thrilled with his task. He and his men,

including his brother Draco (Dean Stockwell) and his bro Bors (Richard Boone),

look down on the Druids because of their pagan

beliefs and the fact that they are peasants.

The knights occupy the keep that overlooks the village. Small scale tale, small scale castle.

Chrysagon meets the village hottie Bronwyn (Rosemary

Forsyth) and he is so confused about his feelings for her that he does not rape

her. When her betrothed Marc comes to

him for the customary permission to marry, Chrysagon reluctantly agrees. Draco reminds Chrysagon of the “droit de

seigneur” which gives nobles the right to sleep with a virgin bride first. He thinks that is a good idea and promises to

return her at dawn. When the sun comes

up and she does not come out, Chrysagon has a rebellious village on his

hands. A rebellious village that makes

an alliance with the Frisians. A rousing

siege of the keep ensues. Ladies, you

get to watch Charleston Heston fight in his loin cloth! Although anachronistic explosions are

eschewed, we still get lots of fire.

This is a strange movie, especially for a movie that

was made before the modern era of realism.

Chrysagon is not an anti-hero, but it is hard to tell whether we are

supposed to view him as a hero. Is it

admirable that he refuses to rape a peasant girl? Is he rewarded with her because of his

restraint? The romance that the movie is

framed around is different, but not necessarily more realistic than in most

medieval movies. I am sure the movie

does not want Bromwyn to be viewed as the villain, but she turns her back on a

man that she seemingly was in love with and then betrays the entire village. Both the central characters show little

concern for the consequences of their actions.

This is justified by way of the common movie trope of “love conquers

all”.

There’s a lot to like in the movie. The acting trio of Heston, Stockwell, and

Boone is strong. Less can be said for

Forsyth. She is in over her head and

does little other than look lovely. There

is some interesting cinematography with some deep focus for the interior scenes

and quite a bit of stationary camera scenes.

The music is almost continuous, but not pompous. The action is what sets the movie on a higher

plane than your typical medieval romance.

I was surprised to find that the movie does clearly fit into the war

movie genre. The assault on the tower is

well done and shifts the movie into a higher gear midway through. The stunt work is noteworthy. There are a lot of falls in the film. The deaths are not laughable and some are

special. One character is impaled by a

tree!

As far as accuracy, the movie deserves some

kudos. The interiors of the keep are

authentically sparse. The clothing is appropriate

for the time period. The knights wear

chain mail, open-faced helmets, and carry kite shaped shields. The siege tactics fit the scenario. The besiegers use a battering ram and a siege

tower. The defenders respond with

boiling oil. There is a bit more use of

bows by the defenders than would be common and the catapult hurling fire balls

is pure Hollywood, but these can be forgiven.

The biggest groaner is the use of droit de seigneur to catalyze the

drama. It tosses in the qualification

that the girl must be returned by dawn.

Not that this is the first or last time a movie will use this disproved

myth to defame the nobility. At least in

1965, the knowledge of this falsehood was not well-known, unlike the egregious

“Braveheart” of 1995. Other slurs on

history include the fact that there would not have been a Druid village in

France by this time. But then we would not get to see what

Hollywood imagined a Druid wedding celebration was like. Lots of dancing,

drinking, and wanton sex. Basically a

frat party. The Frisians were no longer

raiding France in the 11th Century, but at least they don’t have

horns on their helmets.

Although the movie has a mixed record on historical

facts, it gets a lot of credit for the bigger picture of medieval life. It goes out of its way to be realistic on

some aspects of the feudal system. It

clearly depicts the gap between the nobility (even lowly knights) and the

peasants. More rare is the noble family

dynamics that are dramatized. (The movie

is not in a league with “The Lion in Winter”, but what movie is?) Draco is seething with resentment toward his

older brother because being the eldest gave you all the advantages. In general, the movie does a fair job of

showing how unglamorous the time was.

Seamy in a 1965 allowable way, of course.

Does it end up on my 100 Best War Movies list? Possibly.

It certainly belongs on a list of the Top Ten Medieval War Movies. Not that there is a lot of competition.

GRADE = B-

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please fell free to comment. I would love to hear what you think and will respond.