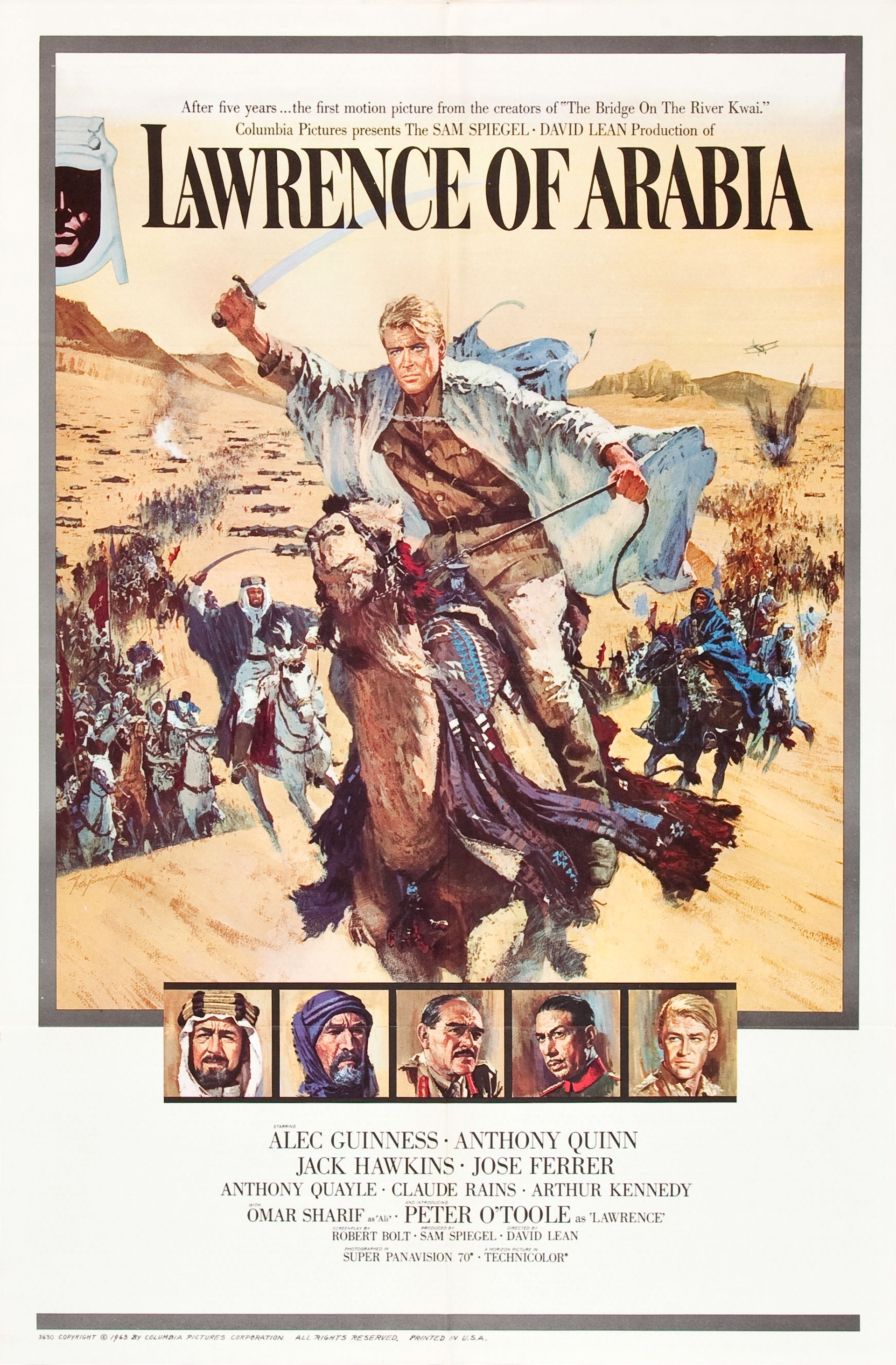

BACK-STORY: “Lawrence of Arabia” is considered one of the

great classic movies. It is #7 on AFI’s

latest list of the greatest movies. It

is #1 on the Epics list. The film is

considered to be the best of director David Lean’s awesome resume (which

includes “Bridge on the River Kwai”). It

is loosely based on T.E. Lawrence’s “The Seven Pillars of Wisdom”. The screenplay was first written by Michael

Wilson, then Robert Bolt was brought in and changed virtually all the dialogue

and characterizations. Wilson was

uncredited partly because he was blacklisted for communist sympathies. His contribution was not credited until

1995. The movie’s desert scenes were

filmed in Jordan and Morocco. King

Hussein of Jordan provided a brigade of the Arab Legion as extras. Peter O’Toole was not the first choice for

Lawrence. Albert Finney was unavailable

and Marlon Brando turned the role down.

Anthony Perkins and Montgomery Clift were considered. Jose Ferrer agreed to appear in it only after

being guaranteed pay that ended up being more than what was paid to O’Toole and

Sharif combined! The movie took over two

years from start to finish. In one scene

the O’Toole that finishes at the bottom of a staircase is two years older than

he was at the top of the staircase. The

desert shoots were difficult. There was

the 130 degree temperatures and the sandstorms and the critters. At one point, O’Toole was thrown from his

camel and only was saved from being trampled by the camel standing protectively

over him. By the way, O’Toole had to sit

on a sponge pad to survive all the riding (the Arab extras called him “Lord of

the Sponge”). It was all worth it as the

film was universally acclaimed. It won

Academy Awards for Best Picture, Director, Art Direction, Cinematography

(Freddie Young), Score (Maurice Jarre), Editing, and Sound. It was nominated for Adapted Screenplay,

Actor (O’Toole lost to Gregory Peck for “To Kill a Mockingbird”), and

Supporting Actor (Sharif).

|

| Drink plenty of water before watching this movie! |

SUMMARY: The rest of the movie is a flashback. Lt. Lawrence is an intelligence officer for

the Arab Bureau in Cairo. An oily

politician named Dryden (Claude Rains) proposes using Lawrence to unite the

Bedouin tribes under Prince Feisal (Alec Guinness) to take on the Turks and

thus open a new front against the Central Powers in the Middle East. The army commander, Gen. Murray, is against

the idea mainly because Lawrence rubs him the wrong way, but Dryden convinces

him he has nothing to lose (other than an insubordinate eccentric). Lawrence’s mission is to locate Faisal and

bring some organization to the Arab Revolt.

Lawrence sets off via camel with

a Bedouin guide. At a watering hole, he

is deguided by the charismatic non-mirage Sherif Ali (Omar Sharif) in one of

the great entrances in cinematic history.

Lawrence chastises Ali for the “littleness” of his people. These two will become best friends and

exchange attitudes by the end of the film.

Lawrence also meets a British military adviser named Brighton (Anthony

Quayle) who considers the Arabs to be “bloody savages”. The Arabophile Lawrence disagrees. When the two Brits reach Feisal’s camp it is

under attack from Turkish biplanes. As per war movie rules, the planes are

dropping extremely accurate bombs that they clearly do not have. The chaotic scene establishes the theme that

the Arabs lack the ability to contend to the modern weaponry of the Turks. Lawrence has some outside the box ideas to

deal with this problem.

Lawrence meets with Feisal and

immediately impresses him with his affinity for Arab culture. He urges Feisal to use his advantages in

mobility to challenge the Turks.

Specifically, Lawrence convinces him to give him some men to attack the

key port of Aqaba from the landward side.

This will entail an almost impossible trek across a desert

affectionately called “the Sun’s Anvil”.

With success in sight, Lawrence defies Ali to go back and rescue an Arab

named Gasim. This suicidal act of

bravery convinces the Bedouin that this guy is special. They reward him with Bedouin clothing and

Lawrence is well on his way to going native.

Al Arauns (as the Arabs call

him) meets a Bedouin chieftain named Auda (Anthony Quinn). Auda is open to joining the revolt as long as

there is money involved. Lawrence

convinces Auda that there is plenty of wealth in Aqaba. The unification almost is aborted by a murder

in the camp, but Lawrence plays peace-maker by executing the culprit who turns

out to be someone Lawrence knows. The

cavalry charge on Aqaba (using 450 horses and 150 camels) is epic in scale and

epicly lensed. (The entire town was

recreated in Spain.) Flush with victory

and feeling increasingly messianic, Lawrence insists on crossing the Sinai

(“like Moses”) with his two servants.

One of them has a date with quicksand.

|

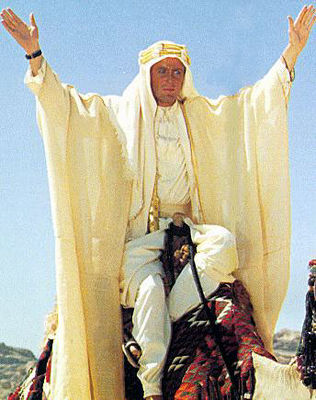

| Look, ma - no hands! |

In Cairo, Lawrence meets with

Murray’s replacement Gen. Allenby (Jack Hawkins). Allenby agrees to Lawrence’s proposal to

launch a guerrilla war against the Turkish railway that they depend on for

supplies. He also wants the Middle East

to be left to the Arabs after the war.

Allenby and Dryden assure him that England has no desire for the region

(wink, wink).

Lawrence is now famous and about

to become a celebrity as an American newsman named Bentley (Arthur Kennedy)

intends to use him to prod the U.S. into WWI.

Bentley tags along as Lawrence attacks trains. Explosives placed on the tracks cause the

trains to wreck and then the Bedouin do the rest. They like loot. The civilized Brighton and Bentley are

incensed by this, but the end justifies the means for Al Aurans.

With the revolt waning, Lawrence

needs an adrenalin rush so he and Ali sneak into Daraa to scout the Turkish

position. Lawrence stands out like a

black man at a Ku Klux Klan rally and is arrested, although not

identified. The Turkish leader (Jose

Ferrer) identifies him as pretty, however.

The audience is left to imagine what happened beyond the caning Lawrence

endures, but apparently Lawrence and the Turk did not play chess. The incident in Daara changes Lawrence and

dampens his enthusiasm for the Arab cause.

Lawrence returns to the British

army which is now in Jerusalem. He is

awkwardly garbed as a British officer again.

Allenby and Dryden inform Lawrence of the Sykes-Picot agreement in which

England and France have decided to establish “spheres of influence” in the old

Turkish empire. Surprise! Lawrence wants no more to do with this slimy

business, but Allenby too easily changes his mind. Lawrence agrees to lead the Arab part of the

campaign to capture Damascus. He tells

Allenby that he intends to take the city for the Arabs to keep. Allenby nods (and thinks – can you believe

how naïve this dude is?).

Al Aurans gathers the tribes and

now has a body guard of thugs surrounding him.

He has gone over to the dark side.

He subsequently orders a “no prisoners” attack on a retreating Turkish

column that had massacred an Arab village.

Lawrence participates looking more manic than messianic. Ali is now the voice of reason and humanity.

|

| "Ali, I see a time soon when the Arabs will be united in a peceful Middle East" |

WOULD CHICKS DIG IT? Yes. It is not a graphic, combat-oriented war

movie. It is more of an epic or biopic than a war movie. O’Toole and Sharif are dreamy. Surprisingly, no females are fawning over

them on the screen. In fact, there is not a single female character in the

movie!

HISTORICAL ACCURACY: This section is going to be a chore. I read “Setting the Desert on Fire” and the

appropriate chapters of the new biography “Hero”, watched the PBS documentary

“The Battle for the Arab World”, and visited several web sites, but there is a

lot of contradictory information out there.

Part of the problem is that the movie is based on Lawrence’s memoirs,

which have been called into question by historians. It is understandable that Wilson used the

book as the outline for the screenplay since Lawrence’s account of his

adventures is compelling, but one has to wonder how much embellishment went

into “Seven Pillars of Wisdom”. I plan

to do a “History or Hollywood” post on the film later, but for now let me

summarize the historical accuracy.

First, the characters. The main characters are all based on real

people or composites of real people. The

composites are Ali (who is based on the actual Sharif Ali, but represents

several Arab comrades of Lawrence’s), Brighton (who stands in for all the

British military advisers), and Dryden (who is typical of British politicians

of the Arab Bureau). Feisal and Allenby

are close to real. Murray is maligned a

bit too much. Although a reluctant

supporter of the Arab Revolt, he later became a strong believer in

Lawrence. Auda gets a raw deal in the

film. Depicted as mainly motivated by

money, he in fact was a patriot. His

depiction as a great warrior is accurate.

Farraj and Daud had roles in Lawrence’s life similar to the movie, but

Daud actually died from freezing to death.

Farraj was put out of his misery by Lawrence, but it was after he was

shot by a Turk. Gasim was a real person

and he was saved from the desert by Lawrence, but he went back for him due to

the Bedouin tradition that one was responsible for his servants. The shooting incident was another

person. Bentley was based on the

American journalist Lowell Thomas who spent about a week with Lawrence and then

wrote glowing tales after the war. He

was not the cynic that Bentley is and did not witness any of the train

attacks. Also, by the time he met

Lawrence, the U.S. was already in the war.

The portrayal of Lawrence has

come under criticism. Some carp about

Lawrence being much shorter than O’Toole, but this can not be a serious

argument against O’Toole getting the role.

No actor on Earth would have been a better choice. Other than height, he resembles Lawrence,

including the blue eyes. The movie

implies that Lawrence wanted the job of meeting Feisal because he wanted to

experience the desert. In reality,

Lawrence had been in the Middle East for some time at this point as an

archeologist and had been coopted by the British Army to conduct a survey of

the Negev Desert. The famous

match-dousing scene alludes to Lawrence’s masochistic tendencies which included

going without food and sleep when he was growing up. The question of Lawrence’s sexuality is

merely hinted at in the film which is appropriate not just because the film was

made in 1962, but because even today it is unclear. Lawrence’s brother, who had sold producer Sam

Speigel the rights to “Seven Pillars”, disowned the film and refused the use of

the book title for the film title.

The assault on Aqaba was not as much

of a surprise as the movie depicts. In actuality,

several Turkish outposts had already been captured and the surrender of the

port had been negotiated. The filmed

charge was true to form, but it occurred after Arab reinforcements arrived and

insisted on it. Lawrence did cross the

Sinai to report to Cairo, but he was accompanied by seven others and no one

died. When Lawrence met with Allenby,

the two got along fine and continued to do so through the rest of Lawrence’s

stay in the Middle East. The

relationship with Lowel Thomas (Bentley in the film) was very inaccurate. He was an unabashed worshiper. It was Thomas who coined the term “Lawrence

of Arabia”.

|

| the assault on Aqaba |

The atrocity at Tafas is pretty accurate. The town had been massacred by a Turkish force

which was then caught retreating by Lawrence’s men. There is some question about whether Lawrence

ordered “no prisoners”. Some historians

argue that he took responsibility for something he could not stop. He did participate. It is ridiculous to make a big deal of this

since it is hard to imagine it playing out differently than what happened.

The closing events in Damascus are

acceptable. Lawrence did enter the city

ahead of the British with the Arab army and he did have high hopes that the

city and the whole of Syria would have its independence. By this time Lawrence knew about British/French plans, but

had kept his knowledge of them from Feisal.

The Arab Council did have trouble administering the city and one of the

problems was lack of electricity.

However, the movie implies that the British were forced to take control

fairly soon when actually Feisal was not deposed until 1920. The last straw incident at the hospital did

occur.

|

| Lawrence at the massacre at Tafas |

CRITIQUE: “Lawrence of Arabia” is a guy epic. All the elements you associate with a movie

of massive scope are there except the mushy romance. The scenery is awesome. Lean was influenced by John Ford’s use of

Monuments Valley and one-ups him here.

I’m not much into scenery, but the desert vistas are incredible. If ever a movie was made to be watched on as

big a screen as possible, this is it.

The cinematography is equal to the locales. Lean contrasts the sere desert scenes with

the cool marble of the British interiors.

The outdoor shots could best be described as sweeping. The movie includes one of the iconic

cinematographic scenes in which Ali appears mirage-like at the watering hole. Add to this the score which matches the

scenes perfectly. No one has ever

deserved the Oscar more than Jarre.

The perfection carries over to the casting. It is hard to imagine any major role that

could have been played better by another actor.

Has any actor ever had a more auspicious start than O’Toole? You have to give the man credit for

preparation as he read “Seven Pillars” almost to the point of memorization and

interviewed as many people who knew Lawrence as he could find. He also learned to ride a camel (Guinness and

Quinn only ride horses in the film.) And

keep in mind that this was Sharif’s first English speaking role. All of the actors acquit themselves

well. There is not an average

performance. Anthony Quinn is great as

Auda and went to great lengthes to look like him. Guinness delivers Feisal’s political bon mots

with aplomb. Quayle does a fine job as

the officer who evolves into an admirer of Lawrence and a person who takes

umbrage at the scheming that daggers the Arabs in the end.

The movie’s themes are

efficiently developed. Lawrence is worn

down from naïve optimism to disillusionment.

His character arc is fascinating and something of a roller coaster ride,

but with the inevitable realization that one man can not change the Middle

East. Early in the film, Lawrence

proclaims to Ali that “nothing is written”, but by the end of the movie it is

apparent to him and the viewer that European domination of the region was written (literally in the

Sykes-Picot agreement). The movie

controversially implies that the Arabs were incapable of governing

themselves. Although one theme is

clearly that the Arabs were shafted by the British, the movie also gives the

impression that the Arabs were too factional and incompetent to rule

themselves. This is reinforced by

Lawrence going from believing that the Arabs can rise above being a “little

people” to being frustrated with having to deal with them. It is interesting to note that Ali and

Lawrence go on opposite arcs as Ali ends up the more optimistic and empathetic

individual.

The movie does have some

weaknesses. It is a bit long with two

lengthy desert passages. In fact, “Lawrence

of Arabia” clocked in as the longest Best Picture winner (one minute longer

than “Gone with the Wind”). In spite of

the length, the combat scenes are too brief.

The movie could have used a few maps and the time frame is hard to

follow. This vagueness was a product of

the decision to concentrate on Lawrence as opposed to the Arab Revolt. Still, the cinematography, acting, plot, and

music stomp out any quibbles.

CONCLUSION: “Lawrence of Arabia” is one of the truly great

motion pictures. Everything about it is

grandiose. It is a film that holds up to

multiple viewings and even though it was made before the VioLingo school kicked

in, it stands up well when compared to the more modern war films. It is interesting to compare it to a film

like “Patton” and see that it is in the same league. I would have to say that “Patton” is the

better war movie, but the lesser movie.

The same could be said when comparing it to Lean’s other war epic –

“Bridge on the River Kwai”. Thus the

conundrum of the list of the Greatest 100.

“Lawrence of Arabia” is firmly ensconced as one of the Top Ten movies of

all time, but is definitely not one of the ten greatest war movies of all time. My opinion is partially based on my belief

that it is not primarily in the war movie genre. I would place it first in the biography genre

and then in the epic adventure category.

I will eventually have to decide if a film like this should be

considered for my 100 Best War Movies list.

RANKINGS:

Acting A+

Action 6/10

Accuracy C

Plot A

Realism A

Cliches A

GRADE

= A

Excellent review and summary. One of your best ones actually as you really dug into this one and it shows. A big part of the grandure of this one is the musical score. One of the best ever done.

ReplyDeleteThanks. And thanks for the book. It was very helpful. I was surprised to find that there are so many different takes on what happened in important events in his life.

ReplyDeleteBTW I'm not sure if many will agree with you on my digging into it. The Internet generation is not into lengthy reading. But then again, that generation would never sit through a movie as long as this. I wonder when was the last time a movie had an overture?

I just looked on Wikipedia and the last significant movie was "KIngdom of Heaven" in 2005. If you do not include "roadshow" versions, there have been only 5 movies since 1970 that had an overture - The Cowboys (!), Jeremiah Johnson, Man of La Mancha, Star Trek, and Kingdom of Heaven.

Deletei like the video

ReplyDeletei like this blog :D

ReplyDeleteThank you. That's nice to hear considering how much work I put into it. I probably spent over 20 hours on this post.

DeleteAs an aside of interest...I noticed there is a new documentary on John Milius out on Netflix you may want to watch since he made a number of war movies. I'm going to watch it this week myself.

ReplyDeleteThanks. I'll look for it.

DeleteActually, the Australian Light Horse had already entered the city and passed straight through at 5am to cut off the Homs Road - well before any Arabs entered Damascus at 7:30am ;)

ReplyDeleteIt was the British Desert Army that did all the fighting pushing back the Turks in the great advance from the 26th of September to Oct 1. The 'Arab Army' did bugger all, very often arriving late or not at all to battles. The Legend of Lawrence and his Arabs was purely for political propaganda purposed to secure Arab support for the war against the Turks.

Sadly - we live with that legacy today. The world would have been a vastly different place if the British didn't make a deal with the devil, so to speak.

Interesting. Thanks.

DeleteI just watched this film for the first time. One word; extraordinary.

ReplyDeleteA little bit in this vein is "Lion of the Desert" with Anthony Quinn. The wikipedia article on this movie says the government under General Gaddafi even helped fund it ( see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lion_of_the_Desert ). Okay, that might not sound too good but the movie seems to get good reviews on the web, it actually captivated me, the last I knew, it was at youtube. It's a movie about the Italian occupation well before WWII and of course, the main character is the "Lion of the Desert", an Arab tribal leader. I'd be interested in your take. It probably makes the mark I'd think. Saw it at youtube and it captivated me. It may not have been shown in the states for some time because of our friction with that country back in the day.

ReplyDeleteThanks. I'll try to get to it. You might want to consider joining my War Movie Lovers group on FaceBook.

Delete