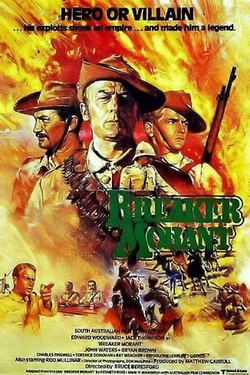

BACK-STORY: “Breaker Morant” was released in 1980 and was the first of three films made in Australia that marked the arrival of Australian cinema as a force in war movies. The other two films were “Gallipolli” (1981) and “The Lighthorsemen” (1987). The film was directed by Bruce Beresford, has an all-Australian cast, and was shot in Australia. It is based on the play by the same name which tells the story of the court-martial of Harry “Breaker” Morant, a well known warrior/poet. It was a box office success in America and was nominated for an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay.

OPENING SCENE: The movie begins with text explaining that the war is set in the Boer War (1899-1902). The war was between the British Empire and the Boers (mostly Dutch settlers) in South Africa. The year is 1901 and the British occupied most of Boer territory, but is having trouble with the mobile Boer guerrillas. “The issues are complex, but basically the Boers wished to retain their independence from England”.

A military band plays in a gazebo in Peitersburg in Transvaal, South Africa. The movie cuts to a court of inquiry involving three soldiers. One of the three, “Breaker” Morant recounts his military career to let the audience know he is a volunteer from Australia who was a distinguished officer. He takes full responsibility for his actions, but claims he was acting under orders.

SUMMARY: The film flashes back to the incident that touches off the inquiry. A small unit of Bushveld Carbineers (a commando unit created by Lord Kitchener to fight the Boers on their turf with their tactics and methods) launches an attack on a farm house supposedly harboring some exhausted Boer guerrillas. It’s an ambush and Capt. Hunt is mortally wounded and left by the retreating British.

Back in the present, at Kitchener’s headquarters in a beautiful mansion, the commander-in-chief meets his hand-picked prosecutor for the upcoming trial. Kitchener tells Maj. Bolton that the Germans are protesting the death of a German mercenary that Morant is implicated in the death of. The Germans are threatening to enter the war to aid the Boers, but really (according to Kitchener) they have their eyes on South Africa’s gold and diamonds. Bolton, with a twinkle in his eye, comments that the Germans “lack our altruism” toward the Boers indicating the hypocrisy of the British position. It is obvious the three colonials will have to be sacrificed for international relations.

|

| the defendants and defender |

A Maj. J.F. Thomas (Jack Thompson) arrives to be defense attorney. Besides the multi-talented Morant (he is a published poet and famous horse-breaker), he also will defend the naively patriotic Lt. George Witton (Lewis Fitz-Gerald) and the roguish debt-escaper Lt. Peter Handcock (Bryan Brown). The trio are bemused to find out that not only has Thomas never handled a court-martial, this will be his first case, period. Indeed, the next morning’s first day of the trial has Thomas looking like an incompetent buffoon until he cross-examines the first witness. At this point the eye-rolls of the defendants turn to looks of admiration. The Carbineers ex-commander had just described the mostly Australian unit as being undisciplined and accuses Handcock of placing train-cars of Boer prisoners in front of trains to stop IEDs. Thomas lays into him getting Robertson to admit the Carbineers were designed to fight like the Boers. And, oh by the way, Robertson had not stopped the practice because it was working.

In another flashback, Morant goes after the killers of Hunt and is visibly upset when he views the badly mutilated body of his friend. He vows revenge and when the find the Boer camp, he leads an immediate charge that results in some intense action and ends with the deaths of several Boers and the capture of one wearing Hunt’s jacket. Morant orders the execution of the prisoner named Visser citing Kitchener’s order pertaining to Boers captured wearing British kit. It is clear, however, that Morant is more motivated by revenge than policy.

At the trial, Morant takes the stand (chair) and maintains that the Carbineers fight by a new set of rules appropriate for this new style of warfare. They did not carry military manuals into the field. As far as the execution, they used the “rule of 303” (a reference to their .303 caliber Enfields) which the audience is left to figure out for itself. Good luck, ladies. (Sorry, I guess that was sexist.) Morant’s killer line is “it is customary in war to kill as many of the enemy as possible”. At this point in the movie, the audience is so firmly in Morant’s corner that most will overlook that Morant is arguing that it is okay to kill enemy prisoners.

The next flashback shows that Hunt had ordered the killing of prisoners and at first Morant had balked until Hunt confirmed that the orders came from Kitchener. The next witness is the Fort Edwards intelligence officer Taylor who testifies that it was common practice to execute prisoners. His testimony is tainted by the fact he is also on trial for executing prisoners.

|

| the accused defending their jail |

The next dawn, the Boers launch a surprise attack on Pietersburg. This is a great scene with lots of gunfire (which seemingly never misses) and some dynamite being thrown by the Boers. One of the Boers is a woman. The trio are released to help in the defense. Handcock shoots a TNT holding Boer who is atop the wall – he blows up. Morant uses a machine gun to stymie the attack. Amazingly no horses were harmed in the filming of this scene, in reality and on the screen.

One of the charges is the murder of a German missionary named Hesse by Morant and Handcock. The missionary has the reputation of collaborating with the enemy. He arrives at Fort Edwards at an awkward moment – Morant has just ordered a firing squad for a group of Boers who had come in under a white flag. When Morant sees Hesse talking with the prisoners, he is enraged and sends Handcock off on a “mission”. Hesse is found dead. The prisoners are stood up against the wall despite the protest of Witton.

When Handcock is called to testify, his alibi for the Hesse murder is he was “entertaining” some ladies at the time. The two ladies are married and to Boers at that. The tribunal of stuffed shirts are appropriately morally repulsed by Handcock, but believe him. Back in jail, Witton is shocked when Handcock admits he killed Hesse. Morant counters Witton’s naivety with a proclamation that “it’s a new kind of war. It’s a new war for a new century.” This new war includes killing civilians, even missionaries. Who do moviegoers side with on this – Witton or Morant?

Thomas’ summation is an anti-war classic. I can’t avoid reproducing part of it here.

"The fact of the matter is that war changes men's natures. The barbarities of war are seldom committed by abnormal men. The tragedy of war is that these horrors are committed by normal men in abnormal situations, situations in which the ebb and flow of everyday life have departed and have been replaced by a constant round of fear, and anger, blood, and death. Soldiers at war are not to be judged by civilian rules, as the prosecution is attempting to do, even though they commit acts which, calmly viewed afterwards, could only be seen as unchristian and brutal. And if, in every war, particularly guerilla war, all the men who committed reprisals were to be charged and tried as murderers, court-martials like this one would be in permanent session. Would they not? I say that we cannot hope to judge such matters unless we ourselves have been submitted to the same pressures, the same provocations as these men, whose actions are on trial."

Although the trio is found innocent on the Hesse charge, they are thrown overboard for the Visser execution and the firing squad of the Boer quitters. In a powerful, sparse scene the three are informed of their fates individually. Death at dawn for Handcock and Morant and a life-time of penal servitude for Witton. Morant sums it up for Witton: “Well, Peter, this is what comes of empire building.”

THE FINAL SCENE: In probably the greatest execution scene in war movie history, Morant and Handcock are led to two chairs in a field. When asked about comforting by a priest, Morant tartly replies that he is a pagan. Handcock: me, too. Morant (ever the Renaissance man) references Matthew 10:36. (“And a man’s foes shall be they of his own household”) With an actual Morant poem in the background, they face their executioners. Morant tells the squad “shoot straight, you bastards. Don’t make a mess of it.” They obey.

RATINGS:

Action - 6

Acting - 10

Accuracy - 9

Realism - 9

Plot - 8

Overall - 9

WOULD CHICKS DIG IT? I think many females would enjoy this movie. Although it has no female characters of note, it is also not overly macho. The action is not bloody or graphic. For instance, we do not see the mutilated body of Hunt. The leads are handsome and charismatic. The anti-war message could have a sort of “I told you so” feel for many women. The courtroom drama aspect of the plot should be appealing.

CRITIQUE: I’ll go out on a limb and proclaim that this is the best movie ever made about the Boer War. You get a feel for the war, although looking it up in an encyclopedia will help with the big picture. It also helps if you are familiar with the Vietnam War because you can transpose that war for much of ”Breaker Morant”. The closing speech by Thomas could have been given by Lt. Calley’s lawyer at his My Lai trial.

In fact, the parallels to the My Lai Massacre (although probably unintentional) are eerie. Calley was also “just following orders”, but could not prove it. Many feel he was made a scape-goat by his superiors. (Like Witton, his sentence was also commuted due to public outrage). Few of Calley’s men refused to obey his orders even though they were obviously inhumane. At least the carbineers were not encumbered emotionally by the Nuremberg dictum that you must disobey unlawful orders to kill prisoners.

The American boys, like Morant, had been changed by the war. If a sophisticated poet like Morant can be corrupted, what can be expected of a nineteen year old grunt? Morant was set off by his best friend’s death, Calley’s men were reacting to recent losses to booby traps. Although Calley’s unit was not the Green Berets (the Vietnam equivalent of the Carbineers), they were fighting the enemy the way he fought them. How many American policy makers in the Vietnam War were familiar with the Boer War? I get the impression America thinks it invented counter-insurgency. The Morant court-martial was known before this movie brought it to the general public. Was it studied at West Point? Did the British Empire look backwards before the Boer War? Were we the new British Empire in the sixties? Are we still?

“Breaker Morant” is also one of the great anti-war movies. I recently got into a debate about whether all war movies are anti-war. Realistically, they should be, but actually a lot glorify war without showing any of the seamier side. The themes of prisoner abuse, never-ending guerrilla war, and scape-goating lower echelon soldiers resonate today. I sure hope this movie is being shown at West Point these days! It would not hurt for cadets to be told to focus on the “war corrupts good men” theme. Officers coming out of West Point are in many ways our “Breaker” Morants. It is the second best “soldiers on trial as scape-goats for command decisions” movie. After watching “Breaker Morant”, pair it off with its sister – “Paths of Glory”.

The only problem I have with the movie is if you really think about it, Morant was guilty of war crimes. Before the death of Hunt, he was clearly conflicted about the verbal orders from higher-up to kill prisoners. When he takes over, he did not have to obey those orders even if he thought they were official and it is clearly implied he became vengeance-minded. It is one of the strengths of the movie that even the death of the missionary seems like a railroaded charge when, of course, it was an egregious breech of the rules of war. How many in the audience see it as it is accurately depicted – an assassination of a priest for choosing the wrong side and for potentially informing on a war crime?

ACCURACY: This all comes down to whether George Witton’s book

Scapegoats of the Empire is truthful. Witton obviously had an axe to grind, but since the transcripts to the trial vanished, he’s our only real source for the trial. His story rings true and most historians have accepted it. The movie is remarkably faithful to the book which means that if you accept the authenticity of the book, the movie is one of the most accurate in war movie history.

The non-trial flashbacks are accurate. Hunt did die in a similar fashion, but he was buried before Morant could see the body. He certainly was told about the mutilations so his anger was certainly accurate. Ironically, historians have since determined that the mutilation was most likely done by black witch doctors! Another slight alteration from the facts was that Visser was not captured wearing Hunt’s jacket, but instead had some British kit in his possession. This makes the real “Breaker” Morant even more unjustified in executing Visser. The dawn attack on the fort did occur and the trio did perform brave enough to get them pardoned, under normal circumstances. The movie includes three of Morant’s poems as proof he was the real deal.

The filmmakers get the little details right. In one scene, a British soldier takes a bath in a wash-tub. Some of the British soldiers wear kilts. The Enfield rifles are accurately depicted. The Boers were famous for their sharp-shooting, although probably not as dead-eye as in this movie. Heck, even the British seldom miss.

CONCLUSION: This is a great movie. The scenery is beautiful as Australia stands in for the unbroken horizons of the Transvaal. The acting is fantastic. In the courtroom scenes, watch the facial expressions of the actors. You can read a lot from those faces! Woodward is seething, Brown is roguish, Fitz-Gerald is naïve, and Thompson is outraged. Denny (the head of the tribunal) and Kitchener are appropriately hissable.

Director Bruce Beresford made a film that is interesting to watch. He uses a stationary camera effectively. He also often has the actor off-center in the frame. He does not use a swelling soundtrack to tell us how we are supposed to feel.

As a history lesson and a lesson in military ethics, the movie is valuable and should be viewed by a public that is at war in a war (Afghanistan) similar to the Boer War. Clearly the film should be mandatory viewing for soldiers involved in a counter-insurgency situation and for the leaders who are fashioning that counter-insurgency policy.

Next up: Battle of Britain

_02.jpg)

_01.jpg)