This is another in my series informing you about how

war movies differ from their source material.

I also take the liberty of comparing the two. I have a belief that a movie should be better

than the novel it is based on and most war movies are. The screenwriter has the advantage of having

the book as his foundation and he can make improvements to the plot and make it

more entertaining. The disadvantage is

that the movie can not go into the detail that a book can.

I am mainly arguing that movies should be more entertaining than the

novel. If you read on, be aware that I

am assuming two things. One, you have

seen the movie already. Two, you are not

planning on reading the book, so you don’t care about spoilers. I hope what you do care about is how the book

differs from the movie and which is better, in my opinion.

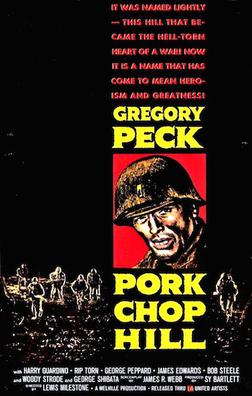

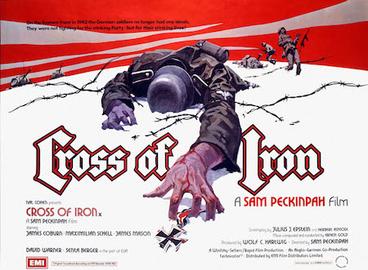

“Cross of Iron” is a war movie directed by Sam

Peckinpah. It is set on the Eastern

Front in WWII. A platoon led by a Sgt.

Steiner (James Coburn) is part of the perimeter defense of a German salient

that is threatened by superior Red Army forces.

Steiner is a great soldier, but is anti-authority and cynical about the

war and the army. His new company

commander Capt. Stransky (Maximilian Schell) has been transferred to Russia so

he can win an Iron Cross. He is a martinet

who realizes Steiner will be a thorn in his side and Stransky is determined to

eliminate Steiner as an obstacle to his medal.

Steiner and his men have to go on a trek behind enemy lines to get back

to their lines after they are left behind in the army’s withdrawal. The movie was based on the novel The

Willing Flesh by Willi Heinrich.

Heinrich served on the Eastern Front and was wounded five times. The screenplay was written by Julius Epstein,

James Hamilton, and Walter Kelley. They

changed the chronology of the book, but adapted some of the key scenes and kept

most of the characters.

The novel opens with Steiner’s platoon in the front

lines of the German perimeter. We are

introduced to his men, who have pretty much the same personalities as in the

movie. For example, Schnurrbart is a

mustachioed rock, Kern is a slacker jerk, Kruger is a slob, Dietz is boyish,

Zoll is a troublemaker (but not the resident Nazi like in the movie). The book has a key character named Dorn who is

an intellectual that Steiner likes to discuss philosophy with. The movie Steiner is more laconic than

philosophical. When the German army

pulls back, Steiner’s group is ordered to stay by his battalion commander

(unlike in the movie where the nefarious Stransky purposely leaves them behind). In the trek back to German lines, Steiner and

crew (they start with eleven men) encounter the Russian female soldiers and the

scene plays out similar to the movie except that at one point Steiner decides

to go off on his own. He changes his

mind and returns after an escaping Russian runs into him. This allows Steiner to avoid the difficult

decision of killing the women to protect their continued journey. Zoll’s rape and death are essentially the

same, but Dietz is not killed until a little later when he runs into a Russian

patrol. Meanwhile, Stransky gets Triebig

to admit he prefers men, but Keppler is not in the room.

When Steiner and the others reach the Russian front

lines, they assault some bunkers with extreme prejudice. They capture a Russian officer and force him

to radio that they are a Russian patrol going out. They proceed into no man’s land and Steiner

goes ahead to identify them and they successfully make it in. Nine of the eleven make it back. Steiner meets Stansky for the first time. He offers to promote him to Sgt., but Steiner

does not react. The conversation enrages

Stransky and it doesn’t help that when he snidely asks if Steiner was an actor

before the war, Steiner responds: “Not

before the war”. (How did that line not

make it into the movie?) Brandt gives

Steiner two weeks R&R. He meets a

nurse who he had an affair with when he was convalescing in a hospital thirteen

months before. It turns out that she had

seduced him and when he dumped her, she framed him for robbery which resulted

in his being put in a penal battalion.

At the rest area, he has an affair with another nurse named Gertrud. Steiner is not a ladies man and the romance

is awkward. While he is gone, Dorn and

Anselm are killed by a random shell.

When he returns, Steiner catches Triebig and Keppler

in bed and beats Triebig up because he had sided with Stransky in the chewing

out of Steiner earlier. The big Russian

attack featuring tanks in the movie occurs at this point. Steiner leads the counterattack with Kruger,

Hollerbach, Kern. and Faber (recruited by Steiner after their return across no

man’s land). The Russians are caught

between two forces and routed. Steiner

is wounded and on the way to the evacuation station, his companion Hollerbach

is run over by a tank. Steiner is away

three months and returns to Schnurrbart, Kruger, Faber, and Maag. He finds out that Stransky is claiming to

have led the counterattack and needs Steiner to sign off on his Iron

Cross. The movie covers the meeting with

the skeptical Brandt, but leaves out a central section where Keisel explains

that Steiner wants time to think on it because Steiner does not want to be a

witness in a court-martial. Keisel

convinces Brandt to drop the matter, but threaten Stransky with consequences if

he doesn’t back off of Steiner. Steiner

has guilt feelings about how he did not appreciate all that Brandt had done for

him, but he did not say he hates all officers, including Brandt.

The big set piece in the book is an attack on a

Russian factory. This is barely

recognizable in the movie in the scene where the Russian tanks break into a

building the platoon had taken refuge in.

Stransky plots with Triebig to kill Steiner in the factory. When Brandt calls to cancel the attack,

Stransky does not pass the word. Steiner

and the men negotiate the maze of corridors in the dark, eliminating the

defenders. Triebig shoots Schnurrbart,

mistaking him for Steiner. Steiner then

insures that Triebig is killed by the Soviets.

Upon returning, Steiner sets up an ambush for Stransky. Brandt is aware, but does nothing to stop

this. Steiner ends up not killing

Stransky and soon after Steiner is wounded by an artillery round and Faber

loses his eyes. At the end of the book,

Stransky is about to be transferred.

Keisel is still with Brandt but he has told him he will be saved to help

start a new Germany. The movie ending is

not even remotely connected to the book.

And since it is a poor ending to a great movie, you have to wonder what

the screenwriters were thinking.

As you can read, the book has more scenes than in the movie. It is unclear why the

screenwriters changed the order of the ones they kept. Subtracting scenes was inevitable, but resequencing

was questionable. The movie jumps immediately into the Steiner/Stransky dynamic

and structures the plot around it. The

book does not really kick into this until midway through, allowing for some

vignettes that develop the whole squad instead of just Steiner. The trek is pushed all the way to the last

third of the book as a way to build to the confrontation between Stransky and

Steiner. The novel is a multi-layered

story of a platoon fighting a losing war whereas the movie is boiled down to a

lost patrol movie with an evil brass cliché.

Steiner completely dominates the movie, but in the book he is the main

character and the rest of the unit get good coverage, too. As you would expect, the novel fleshes out

the characters quite a bit more than the movie.

The movie does borrow the basic personality traits, but the novel

actually puts you into the characters’ heads and Heinrich gives each member of

the platoon a chance to have their moment.

Most importantly, Steiner is a multi-dimensional character, unlike the

simply cynical, laconic movie Steiner.

Heinrich’s Steiner is mercurial.

He even pouts occasionally. He is

quick-tempered and unstable.

Significantly, for those of you who care about motivation, we find out

why Steiner is the way he is. He lost

his fiancé in mountain climbing accident that would scar anyone. There was also that frame-up by the nurse. Another difference between the movie platoon

and the novel platoon is that in the book the men are much more

dysfunctional. They are far from a band

of brothers. Some of them hate each

other and not all are enamored with Steiner, although all recognize that

without him they are doomed.

The movie does retain the Brandt/Keisel dynamic, but

obviously the book includes much more of their interesting discussions. Keisel is one of my favorite fringe

characters in war movies and Brandt is a key figure in the theme that even some

of the German leaders were cynical. It

was certainly unfair when Steiner lumped him in with all officers. At least in the book, Steiner is

remorseful. Keisel is the conscience of

the book (along with Dorn). Keisel

defines courage thus: “In 99 out of

100 cases, courage is nothing more than expression of common politeness or

sense of duty. [The other 1%] is an expression

of insanity.” Keisel gets almost as much

ink as Stransky, since Stransky is a smaller character than in the movie. However, the movie does give us the full

Stransky. By the way, there is no

Russian boy-captive in the book. I would

have to give the movie that one.

I have mentioned that in most cases I believe that

war movies based on novels are better than the novel. However, “Cross of Iron” is not one of those

movies. The main reason why the book is

superior is because it is able to flesh out all the characters. Even the main character is more

multi-dimensional and less mysterious.

Clearly, a book should do this better than any movie, but the main

reason why the movie is inferior is the dubious decisions on changing the

sequence of events in the book’s plot.

It would have been much smarter to use the novel as an outline and then

eliminate scenes due to time pressures.

The movie wisely condenses the theme to glory-hunting (Stransky) versus

cynical survival (Steiner) and focuses on that aspect from the get-go. It is pretty effective in that single-mindedness,

but blows it in the end with the ridiculously unrealistic ending that sees

Steiner abetting Stransky. To have the

officer-hating Steiner kill Triebig for killing his men and then have him spare

the much more odious Stransky is bizarre.

Heinrich’s Steiner also spares Stransky, but in a much more believable

manner. And having Stransky get his

transfer hammers Heinrich’s own cynical attitude toward the war he fought in.

BOOK = A

MOVIE = B+